We all face different kinds of uncertainty every day. Those unknowns can entirely change our choices, and outcomes.

In some situations, you can't reduce the unknown, but in others you can. Depending on the circumstances or your experience, that little bit of effort might make a huge difference, or a small one.

This is the first of three posts about the process of reducing uncertainty. Here, I focus on the balance between the degree of uncertainty and the amount of effort it takes to reduce it.

I call these variations “learning curves of the unknown.”

Let’s start with a simple example. Maybe you’re planning to meet a friend for dinner. You agreed on a tentative time, but it depends when they get off work and how bad traffic is. So you text to get an updated ETA and adjust. In that situation, the learning curve might look a bit like this:

Figure 1 – Learning curve graph which starts with high uncertainty, but very quickly drops to almost none.

Now let’s suppose you want to buy a lottery ticket. Unfortunately, the lottery is a different kind of uncertainty. In technical jargon it’s called “aleatoric” uncertainty, which just means you can’t really reduce it by learning. In this case, the learning curve picture will look like this:

Figure 2 – Learning curve graph where the uncertainty stays the same for any amount of effort.

These two situations, learnable (epistemic) and unlearnable (aleatoric) are what most people think about when faced with a decision. However, expertise will actually change our learning curves.

Like most ideas I like, this is a meta-idea. Learning curves are typically drawn as the journey from beginner to expert. But, if you think about a junior programmer trying to estimate how quickly they’ll be able to get a task done, there is a mix of learnable and unlearnable uncertainty (see figure 3).

Figure 3 – Learning curve graph where the initial learning is almost none, and then gradually reduces the uncertainty to be about half of the original unknown.

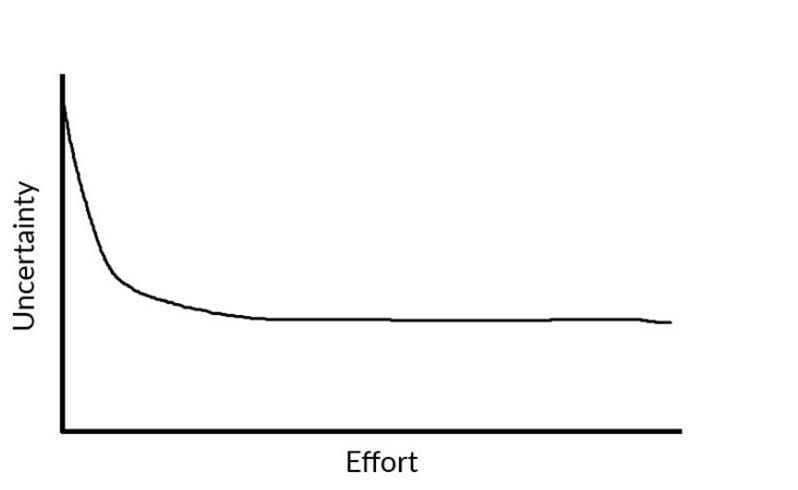

Now compare that picture to what it looks like when you’re an expert programmer (see figure 4). Both roles start with the same amount of uncertainty, but the pictures rapidly diverge. Experts know the questions to ask, and they know the implications of the answer. They figure out all the learnable uncertainty much faster and are left just with the remaining unlearnable portion.

Figure 4 – Learning curve graph where just a small amount of effort eliminates half the uncertainty.

This picture I’ve had in my head is a key part of how I assess the unknown. First, I need to figure out if this is a learnable situation of not. If it is, the next step is to understand what options we have to reduce the uncertainty and how much effort if might take to do so.

In my next post in this short series I will explore the value of decision trees in navigating uncertainty.